Writing gets your science on the page. Positioning gets it accepted, read, and cited.

What if the real reason your paper got rejected was because no one cared?

I know, you care. Your lab cares. Maybe even your mom cares. But the journal editor? Reviewer #2, who just slammed you in three sentences of unactionable “feedback” They didn’t care.

Because you didn’t make them.

If I had a dollar for every time I heard, “But the writing was good!” when breaking down an article rejection with a client, my bank balance might look something like the budget of your last grant application. It’s all too easy to assume that if a paper is written clearly, logically, and grammatically, the science will speak for itself.

But science can’t speak. You have to be its voice.

Even the best-written article that’s ever articled won’t make it past the desk if it sounds like a solution to a problem that nobody thinks they have. In contrast, several articles that are honestly a bit shit, actually, have made it into our news feeds because they’ve been written in a way that makes it sound like they’re addressing an issue that people care about right now.

You need positioning.

Let me give you an example that might be slightly controversial. We’ve all heard the story about how Watson and Crick scooped Rosalind Franklin and stole her data on the structure of DNA. There is some truth to that, and also some misinterpretations regarding collaboration—I’ll let you look it up and decide for yourself. My focus here is the titles and first paragraphs of their articles on DNA structure, which, incidentally, were published back-to-back in the same issue of Nature:

Watson & Crick:

“Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid”

We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.

Franklin & Gosling:

"Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate"

Sodium thymonucelate fibres give two distinct types of X-ray diagram. The first corresponds to a crystalline form, structure A, obtained at about 75 per cent relative humidity; a study of this is described detail elsewhere(1). At higher humidities, a different structure, structure B, showing a lower degree of order, appears and persists over a wide range of ambient humidity.

Which one would you read? Which one would you remember?

This is a perfect example of why positioning is critical in scientific writing.

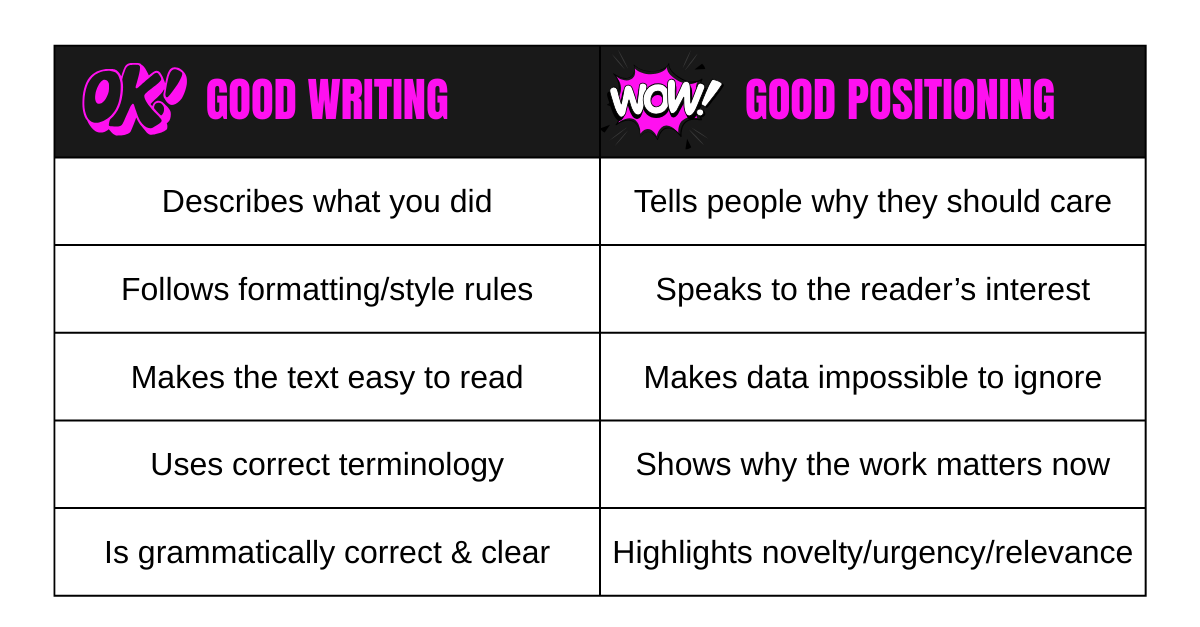

Good writing shows people what you did. Good positioning shows them why they should give a damn.

A well-written introduction walks the reader through the background and research question. A well-positioned intro opens with a problem and says, “We solved it.”

A well-written discussion explains the findings and compares them with previous work. A well-positioned one does this in a way that spotlights the impact of the study’s findings and refocuses the reader back to their significance in the context of the broader field.

But I’m a scientist, not a marketer! — you, probably.

Unfortunately, every time you write a paper and submit it, you’re marketing your science. You’re selling a story. Imagine you’re pitching it to a news outlet—why does your research matter? Why does it matter now? Who does it help? What does it solve? Inject those aspects into the most important sentences in your paper, and you might find that Reviewer #2 cares just a little more (don’t expect miracles, of course…).

Where does positioning matter most?

Your title and abstract

You’ve got people’s attention for about 30 seconds here. Maybe 0.3. Ask yourself:

Does this title highlight the why as well as the what?

Does this abstract tell the story or just present facts?

Would you keep reading this if you came across it in the wild?

Your Introduction

It’s not just a literature review. It sets the stage for the rest of the paper. Yes, some questionable types might ignore the introduction entirely and look at the figures before anything else in the paper (hi, I’m questionable), but most people are going to be looking in that intro for a reason to keep reading. Ask yourself:

Does this intro clearly show the real-world or field-level problem I’m addressing?

Does it explain who else works on this stuff and what I’m seeing that they’re not (nicely, of course)?

Am I clearly stating why this work is important right now?

Your Discussion

This is the mic-drop moment. You know that feeling when you’re awake at midnight imagining yourself delivering one of the 10 witty comebacks you thought of too late to use in the last committee meeting? (It’s not just me. I know it.) Bring that energy to your discussion. Ask yourself":

Have I explained what impact this work has or could have on my field (or on clinical practice, or for policy, etc.)?

Have I connected this impact to wider conversations?

Does my phrasing indicate sufficient (and not widely overstated) confidence in my work’s value?

Don’t rely on people picking up on hints. People are bad at this. Like really bad. Reviewers and readers are only going to take from your work what you explicitly tell them you want them to think.

Do you want them to think you’re filling a knowledge gap, or do you want them to think you’re building new approaches and solving problems?

Do you want to suggest future research directions, or do you want to highlight the importance of your work to a high-impact future outcome?

Do you want to align with previous findings or reframe and advance the conversation?

Do you want people to talk about that article I read last year or “Bartlet’s awesome study on the secret plan to fight Reviewer #2”?

Your move.